by Jo Swenson

In the 180 years following the first publication of Shakespeare’s sonnets, the famous poems underwent some major revisions. While most modern readers are unaware of this historical editing of the sonnets, much can be learned not just about the poems and their reception in the 17th and 18th centuries but also about the early modern editorial tradition and the lasting impacts it has had on the way we interact with these texts.

Essential to understanding the early editorial history of the sonnets is to look at the poems themselves. This post will examine the three most influential editions of the sonnets from the first 200 years of their existence; The 1609 Quarto Shake-speares Sonnets Neuer before Imprinted, John Benson’s 1640, Poems VVritten By Wil. Shake-speare, gent., and Edmond Malone’s 1790 “The Plays and Poems of William Shakespeare.”

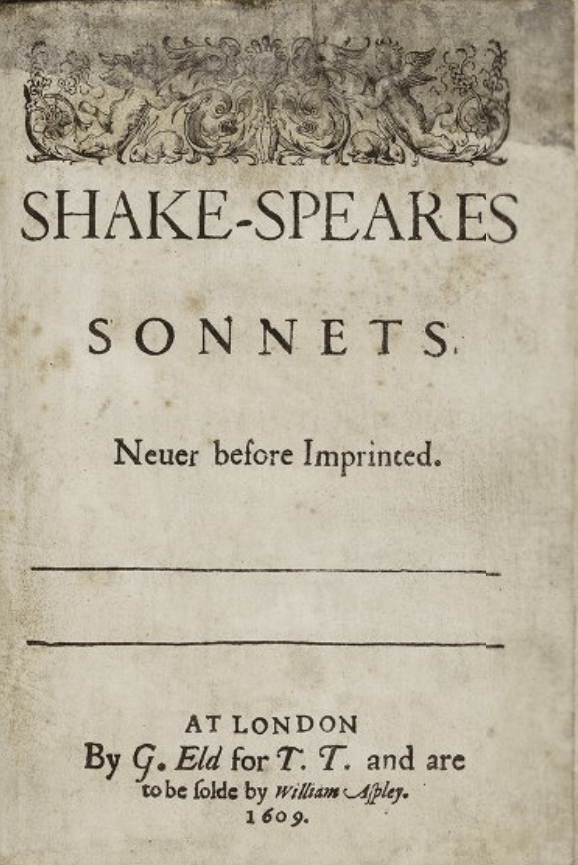

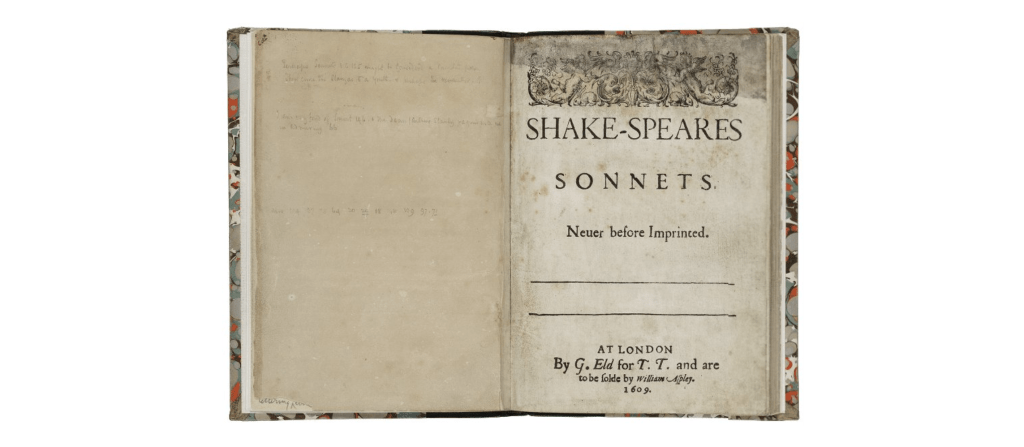

Shake-speares Sonnets Neuer before Imprinted

William Shakespeare, Shake-speares Sonnets (London, Thomas Thorpe, 1609), https://luna.folger.edu/luna/servlet/s/9d2qxf.

Shakespeare’s sonnets were first published in 1609 in London by a man named Thomas Thorpe. This quarto edition contained 154 sonnets and the poem A Lover’s Complaint.1

The quarto also included the following dedication,

William Shakespeare, Shake-speares Sonnets (London, Thomas Thorpe, 1609), https://luna.folger.edu/luna/servlet/s/9d2qxf.

It is not clear whether this dedication or anything else in this edition was authorized by Shakespeare himself. That said, as it is the earliest edition and the only one published within Shakespeare’s lifetime, it serves as the definitive edition against which all later editions will be compared.

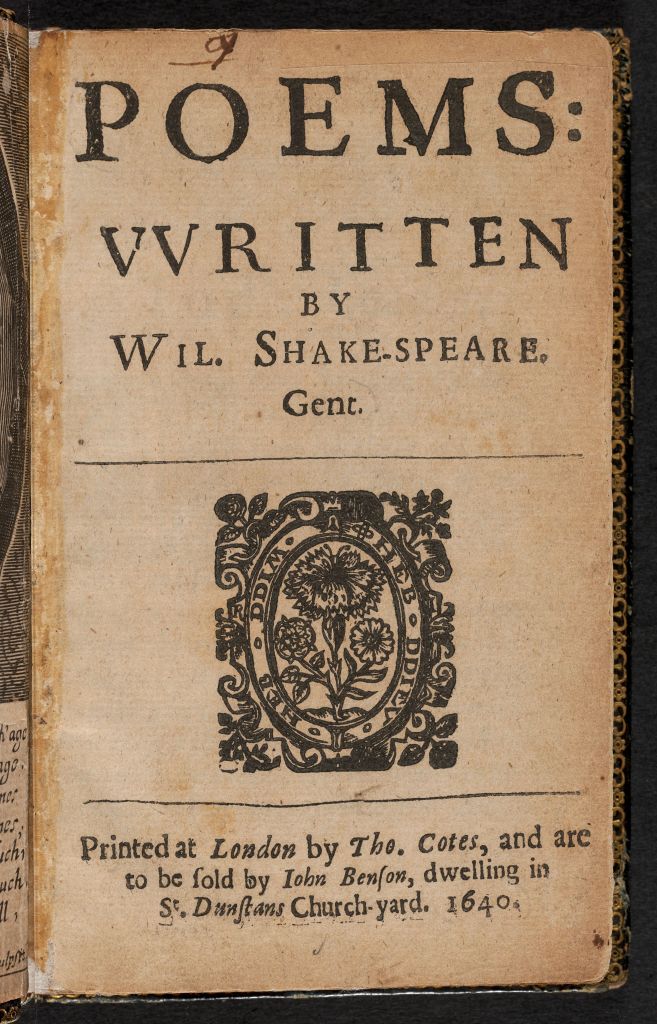

Poems VVritten by Wil. Shake-speare, gent. 1640

William Shakespeare. Poems vvritten by Wil. Shake-speare, gent. (London, John Benson, 1640), https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/qb98pz027.

Shakespeare’s sonnets were not published again until 1640, they do not appear in the famous first folio that collected many of Shakespeare’s other works. In 1640 the sonnets were published by John Benson in London under the title Poems VVritten by Wil. Shakes-peare, gent. While Benson assured readers in his introduction that the poems “appear in the same purity, the Authour himselfe then living avouched, “2 the poems appeared drastically different from those that appeared in the 1609 quarto.

The most notable difference is that the poems are no longer 14-line sonnets. In his edition, Benson combined, usually between two and three sonnets, to create longer poems that were printed under titles created by Benson. These poems included 146 of the 154 sonnets that appeared in the 1609 quarto.3 It is unclear why Benson removed 8 sonnets as well as the dedication from his edition.

In addition to the edited sonnets, Benson also included poems from The Passionate Pilgrim, a collection of poems published in 1599 that were attributed to Shakespeare originally, but most modern scholars agree only a few of the poems in the collection were truly written by Shakespeare.4

Benson also made minor but significant edits to the language in two of the sonnets. In both sonnets, changes are made to the language used to address the beloved.

It is worth looking at the Benson edits closely because understanding the changes made will inform our understanding of how and why these edits were made.

Titles

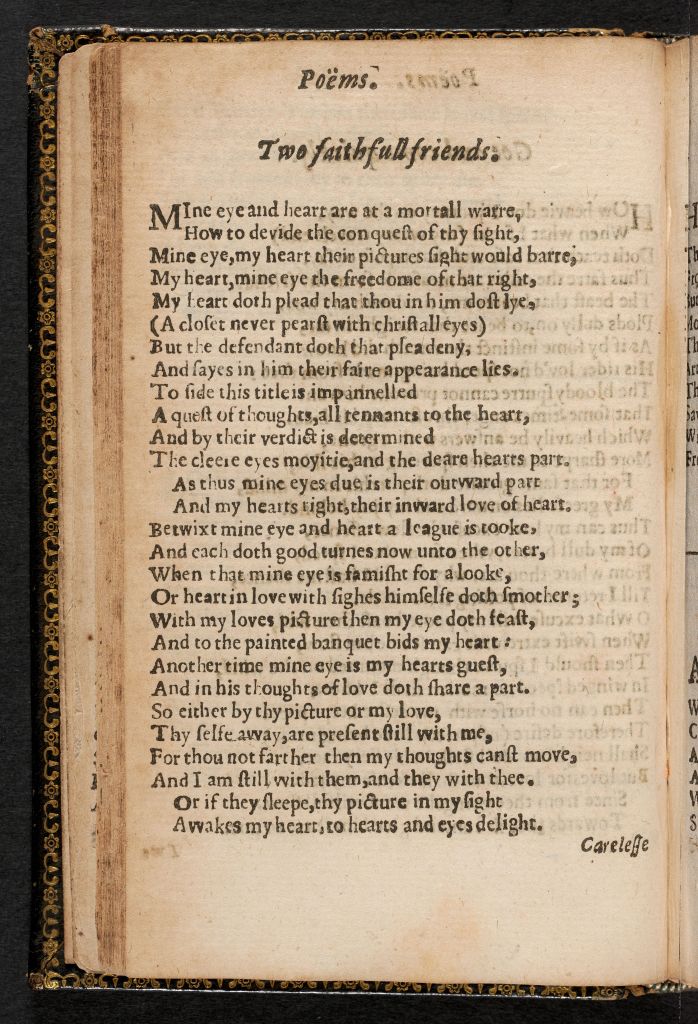

As mentioned above, Benson added his own titles to the poems he created with the sonnets. Some of these titles are misleading. The first title that stood out to me was the one Benson added to Sonnets 45 and 46.

William Shakespeare. Poems vvritten by Wil. Shakes-peare, gent. (London, John Benson, 1640), https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/qb98pz027.

Benson calls these combined sonnets “Two faithfull friends.” These poems include lines such as,

“For thou not farther than my thoughts canst move,

And I am still with them, and they with thee.

Or if they sleepe, thy picture in my sight

Awakes my heart, to hearts and eyes delight.”5

All poetry is open to interpretation, but these two sonnets seem to clearly be love poems. It is interesting that Benson chose to give them a title that implies they express nothing more than friendship. A later post on this blog will address some of the different theories about why Benson made the choices he did, but it is worth noting here that while Sonnets 45 and 46 do not use gendered pronouns for the beloved, they fall within the first 126 sonnets that are generally thought to be addressed to a man. Similar titles can be found elsewhere in the text. Misleading titles are added to other fair youth poems. Sonnets 113, 114, and 115 are given the title “Selfe flattery of her beautie” and Sonnet 122 is called “Vpon the receit of a Table booke from his mistris.”

Word Choice

Only two sonnets in Benson’s poems had their contents edited. While the changes are few they are significant and worth exploring.

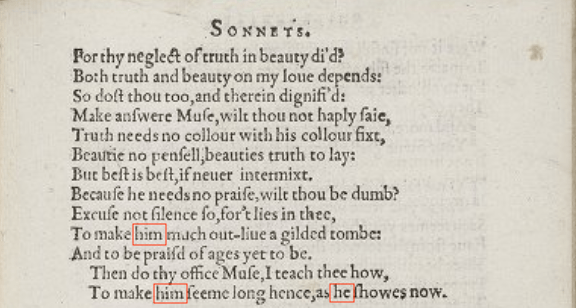

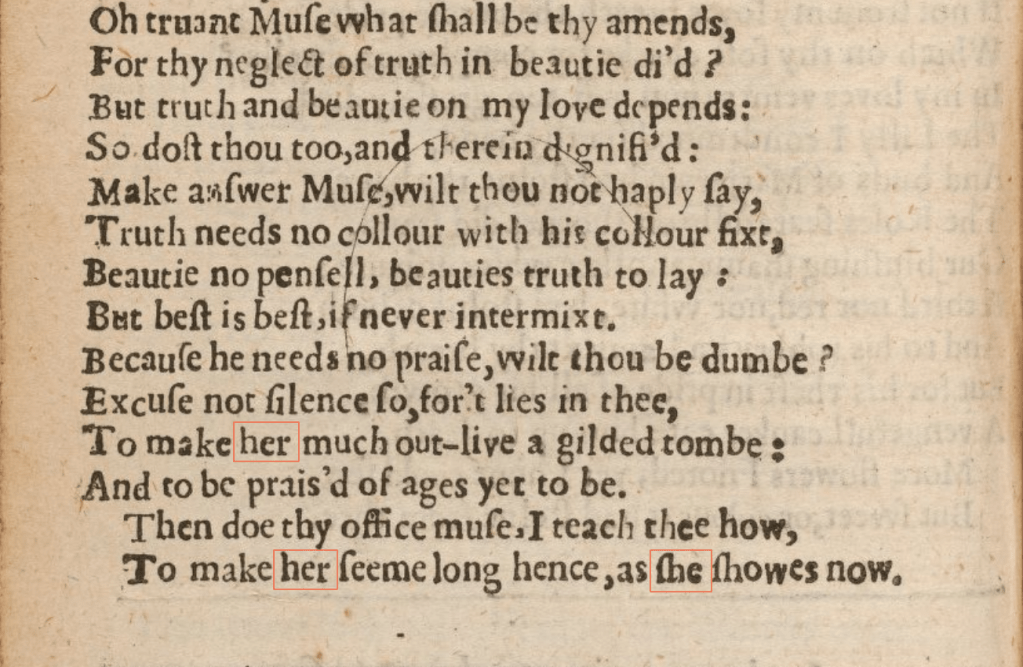

Benson combines Sonnets 100 and 101 into one poem he calls “An invocation to his Muse.” Within Sonnet 101 Benson changes the pronouns he and him to she and her. The changed pronouns are highlighted with red boxes in the images below.

Sonnet 101 in 1609 Quarto

William Shakespeare, Shake-speares Sonnets (London, Thomas Thorpe, 1609), https://luna.folger.edu/luna/servlet/s/9d2qxf.

Sonnet 101 in Benson’s Poems

William Shakespeare. Poems vvritten by Wil. Shakes-peare, gent. (London, John Benson, 1640), https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/qb98pz027.

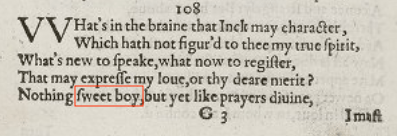

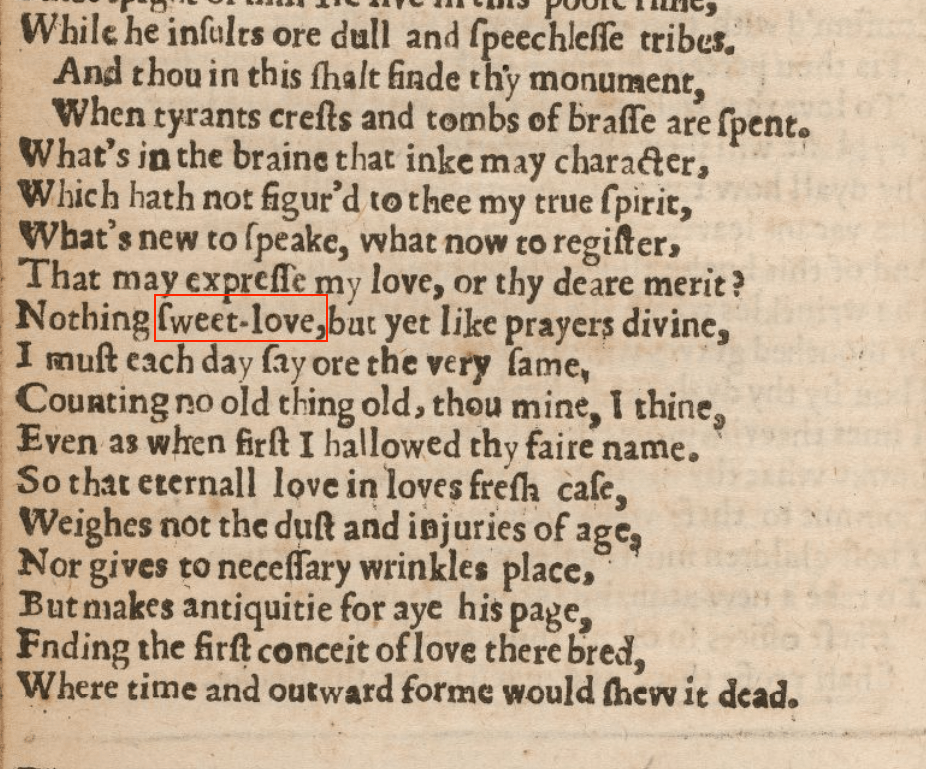

The other sonnet that Benson edited was Sonnet 108. Sonnet 108 is combined with Sonnet 107 under the title of “A monument to Fame.” The line, “Nothing sweet boy, but yet like prayers diuine,” is changed to, “Nothing sweet-love, but yet like prayers divine.” This change can be seen in the images below, changes are again highlighted with red squares.

Sonnet 108 in 1609 Quarto

William Shakespeare, Shake-speares Sonnets (London, Thomas Thorpe, 1609), https://luna.folger.edu/luna/servlet/s/9d2qxf.

Sonnet 108 in Benson’s Poems

William Shakespeare. Poems vvritten by Wil. Shakes-peare, gent. (London, John Benson, 1640), https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/qb98pz027.

The possible reasons for these changes, as well as the addition of misleading titles with be explored in greater depth in a later post, but some have argued that these edits are motivated by a desire to obscure the queerness* of the poems.6 For now, it is important to consider the choices Benson made because they had a lasting effect on The Sonnets. Most editions of The Sonnets over the next 150 years would be based not off of the 1609 quarto but off of Benson’s 1640 Poems.

It was not until 1790 that The Sonnets returned to their original form in a collected works of Shakespeare created by editor Edmond Malone.

* It is important to acknowledge that understandings of homosexuality have changed dramatically between the 17th/18th centuries and today. I am using the term “queer” to refer to the love between men expressed in The Sonnets, knowing that this term would not have been used at the time of any of these editions.

The Plays and Poems of William Shakespeare

In 1790 Edmond Malone published a ten-volume set entitled The Plays and Poems of William Shakespeare. The Sonnets were included in Volume 10 alongside the poems “Venus and Adonis,” “The Rape of Lucrece,” “The Passionate Pilgrim,” “A Lover’s Complaint,” and the plays “Titus Andronicus” and “Romeus and Juliet.” His version of The Sonnets first appeared in 1780 as a supplement to the Steevens-Johnson edition of the collected works published in 1778.7 This supplement was not part of the edition proper, and it was not until Malone’s 1790 edition that this version of The Sonnets was widely read. For purposes of this blog we will be looking at the 1790 edition.

In this 1790 edition, The Sonnets are returned to a form more closely aligned with the 1609 quarto, Malone makes some minor edits to spelling, but the content remains the same. The poems once again are divided into 154 fourteen-line sonnets without titles. Malone also returns Sonnets 101 and 108 to their original language.

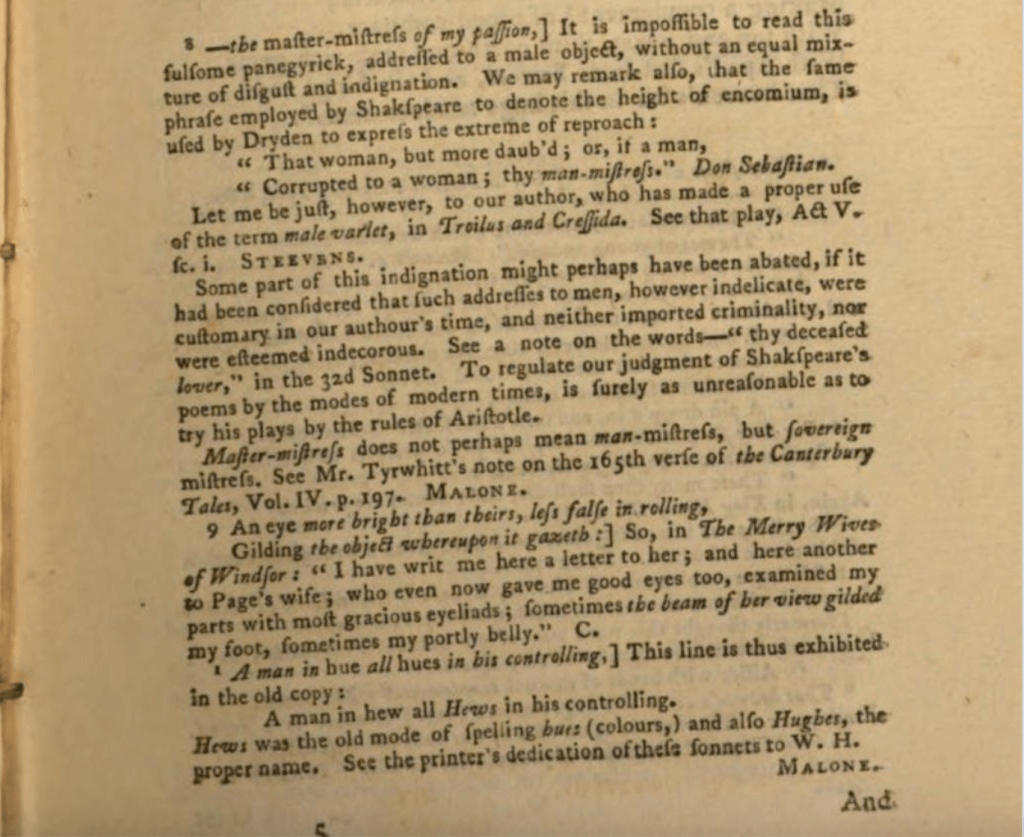

Malone’s editorial hand is visible throughout the text with extensive footnotes that, at times, take up more space on the page than the sonnet he is commenting on. Malone includes commentary from fellow Shakespeare editor George Steevens with Malone’s comments acting as a response to Steevens.

Throughout his footnotes, Malone takes pains to tie the content of The Sonnets to Shakespeare himself. He tries to tie different Sonnets to particular moments in the poet’s life. Malone also includes extensive references to lines in Shakespeare’s plays that use similar language to that of the Sonnets. Much of the work Malone is doing in his footnotes is trying to establish the Sonnets as part of the greater Shakespeare canon.

Looking into Malone’s commentary on just the sonnets themselves could be its own blog, but it is the comments on Sonnet 20 that I want to focus on here. While there is debate regarding whether Benson’s edits were purposefully obfuscating queerness, there is little question as to Malone’s stance on the queerness of the Sonnets.

William Shakespeare. The Plays and Poems of William Shakespeare. ed. Edmond Malone (London: 1790). https://books.google.com/books?id=nEArAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

In a footnote to the line, “Hast thou, the master-mistress of my passion,” Steevens writes,

“It is impossible to read this fulsome panegyrick, addressed to a male object, without an equal measure of disgust and indignation.”8

In response, Malone states,

“Some part of this indignation might perhaps have been abated, if it had been considered that such addresses to men, however indelicate, were customary in our authour’s time, and neither imported criminality, nor were esteemed indecorous.”9

Steevens is more outrightly disgusted by the queerness of this line while Malone tries to explain it away. Malone makes the age-old argument that this was simply how men spoke to one another at the time, an argument that has been made today about Malone’s own time. Yet he felt it was important to include Steevens’ condemnation in this edition.

Throughout his comments, Malone argues that The Sonnets are autobiographical in nature which makes this dismissal of same-sex attraction interesting. If his overall argument is that The Sonnets express Shakespeare’s true feelings, he must dismiss the queerness of this line in order to save Shakespeare from the indignity of accusations of same-sex attraction.

Now that we are familiar with the three texts that informed the 17th and 18th-century interpretation of The Sonnets, it is time to look at the act of editing in this period and the editors themselves.

Bibliography 1. William Shakespeare. Shake-speares Sonnets. (London: Thomas Thorpe, 1609), https://luna.folger.edu/luna/servlet/s/9d2qxf. 2. William Shakespeare. Poems vvritten by Wil. Shakes-peare, gent. (London: John Benson, 1640), https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/qb98pz027. 3. Margreta de Grazia, “Individuating Shakespeare’s Experience: Biography, Chronology, and the Sonnets,” in Shakespeare Verbatim (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 132-176. 4. “Shakespeare the Poet,” Shakespeare Documented, accessed December 9, 2022. https://shakespearedocumented.folger.edu/resource/shakespeare-poet. 5. William Shakespeare. Poems vvritten by Wil. Shakes-peare, gent. (London: John Benson, 1640), https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/qb98pz027. 6. Peter Stallybrass. “Editing as Cultural Formation: The Sexing of Shakespeare’s Sonnets,” in Shakespeare’s Sonnets: Critical Essays, ed. James Schiffer (New York: Routledge, 1999), 75-88. Kindle. 7. Margreta de Grazia, “Individuating Shakespeare’s Experience: Biography, Chronology, and the Sonnets,” in Shakespeare Verbatim (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 132-176. 8. George Steevens, footnote in The Plays and Poems of William Shakespeare, ed. Edmond Malone (London: 1790), https://books.google.com/books?id=nEArAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false. 9. Edmond Malone, footnote in The Plays and Poems of William Shakespeare, ed. Edmond Malone (London: 1790), https://books.google.com/books?id=nEArAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false.

A full bibliography can be found at https://editingshakespeare.com/2022/12/16/bibliography/

Leave a comment