by Jo Swenson

It was not until the 20th century that the editorial history of the Sonnets was revisited. This post deals mostly with Benson’s edition as it has caused greater debate amongst scholars but Malone’s edition is almost always present in critiques of Benson.

Hyder Rollins and Lord Alfred Douglas

Many cite Hyder Rollins’s A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare – The Poems as the originator of the debate that now surrounds John Benson’s Poems VVritten By Wil. Shake-speare, gent.

In his 1938 edition, Rollins states regarding Benson’s edits, “Many of which are designed to make nearly all the sonnets refer to a woman, as where fair love is substituted for fair friend, sweet love for sweet boy.”1 As Margreta de Grazia will later point out, Rollins’s footnote is misleading.2 He makes it seem as though there are countless examples of this gendered editing when, as seen in the first post of this blog, only three Sonnets were edited in this way (though more were burdened with misleading titles). While Rollins’ points should not be dismissed outright due to this exaggeration, it does beg the question of why Rollins wanted to address Benson’s alleged concealment of queer desire in the Sonnets. An earlier text that Rollins quotes in his New Variorum Edition may shed some light on this.

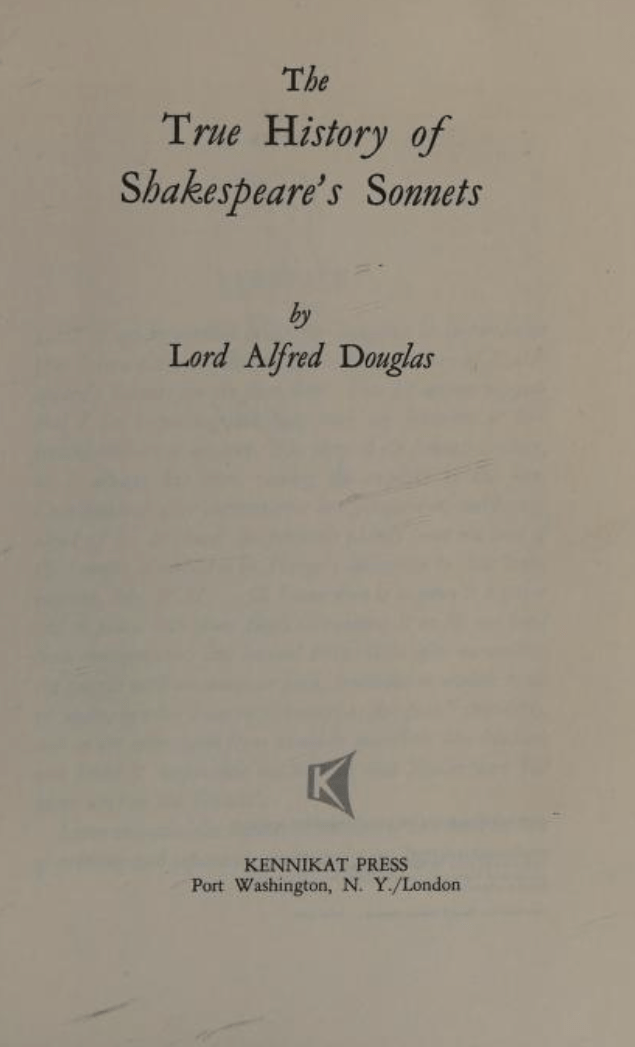

In the same footnote in which Rollins claims edits were made “to make nearly all the sonnets refer to a woman, “3 he also quotes from the 1933 book The True History of Shakespeare’s Sonnets by Lord Alfred Douglas.

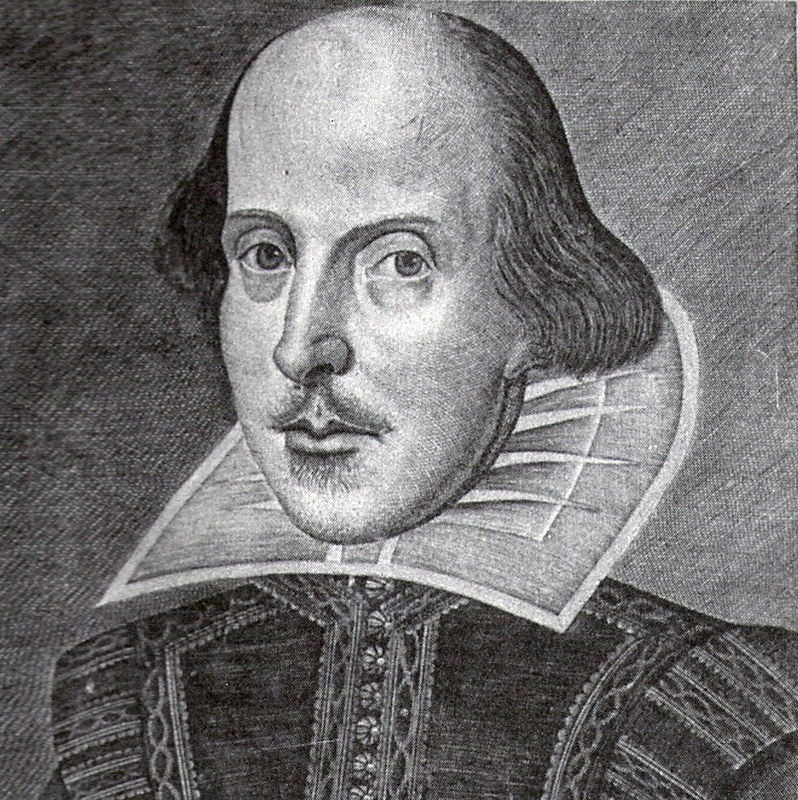

Lord Alfred Douglas was a poet and writer but is today best known for his relationship with Oscar Wilde. The two started an affair in 1892 when Douglas was 22. When Douglas’s father, the Marquess of Queensberry, learned of the affair, he worked tirelessly to separate Wilde from his son. He publicly called Wilde a sodomite. Douglas encouraged Wilde to bring a libel suit against his father. This suit resulted in Wilde being brought to trial on charges of gross indecency with another man and ultimately sentenced to two years of hard labor. While imprisoned wrote letters blaming Douglas for his downfall. These letters would later be published under the title De Profundis.4

In his book, Douglas describes Benson’s poems as a “mutilated and bowdlerised edition.”5 Later in the same chapter, Douglas quotes from his own autobiography, referring to letters written by Wilde,

“There is nothing in his [Wilde’s] letters which could be matched in Shakespeare’s sonnets (also written to a boy), and though I believe it is the fashion nowadays to accuse Shakespeare of having the same vices as Wilde, this merely shows the baseness and stupidity of those who make such accusations on such grounds”6

It is fascinating to see the man who coined the term, “the love that dare not speak its name, “7 so vehemently deny a queer reading of the Sonnets.

The fact that Rollins chose to back up his claim that Benson was concealing queer desire with his edits by quoting from a book by a man who clearly states that he does not believe there is any queer desire to be found at all. If Douglas was correct in stating that it was in fashion to read Shakespeare as queer, Rollins’s decision to reexamine Benson’s gendered edits makes sense. Additionally, in the 1940s, interest in Oscar Wilde was on the rise, with the first full publication of De Profundis coming in 1949.8 This interest in revisiting queer texts may have influenced Rollins’s choice to write about Benson’s Poems.

Margreta de Grazia

Margreta de Grazia published her refutation to Rollins in her 1993 article “The Scandal of Shakespeare’s Sonnets.” As mentioned above de Grazia points out that Rollins’s statement about Benson’s edits made it seem like gendered language was changed in all of the Sonnets rather than just three. de Grazia goes on to point out that it is actually Malone who divided the Sonnets at Sonnet 126. This is true, Malone’s footnote to Sonnet 127 reads, “All the remaining sonnets are addressed to a female.”9 This division has followed the Sonnets ever since Malone’s edition, and de Grazia makes the point that while none of the first 126 sonnets are addressed to a woman, and none of the last 28 are addressed to a man there are many sonnets that do not state the gender of the beloved.

de Grazia’s main argument focuses on the last 28 sonnets. She argues that the true scandal of the Sonnets is found in these later poems that express not just extramarital sex but sex between classes and possibly races. de Grazia writes, “As the law itself under Elizabeth confirmed by more severely prosecuting fornication between men and women than between men, nothing threatens a patriarchal and hierarchic social formation more than a promiscuous womb,”10 she continues a few paragraphs later, “The patriarchal dream of producing fair young men turns into the patriarchal nightmare of a social melton pot, made all the more horrific by the fact that the mistress’s black is the antithesis not just of fair but of white.”11

Concluding Thoughts

de Grazia makes a thought-provoking argument that we view the Sonnets through a modern lens of scandalous behavior rather than an early modern lens. Yet she implies that because the later Sonnets contain scandalous material, then the earlier Sonnets were not scandalous. Robert Matz argues in his 2010 article “The Scandals of Shakespeare’s Sonnets,” that it is possible for the Sonnets to include multiple scandals.12

Ultimately this is the side I find myself most aligned with. Yes, Benson’s edits were few, but they were made for a reason. They all appeared in the first 126 Sonnets, and they were always changing explicitly male terms of address to either female or neutral terms. Simply because the later sonnets were also, and perhaps in their time, more scandalous than the earlier poems does not mean that there was no scandal in the fair youth sonnets, nor does it mean that Benson was not trying to conceal queer desire with his edits.

In April 2019, the British Library tweeted the following about their copy of Poems VVritten By Wil. Shake-speare, gent. bringing Benson’s legacy as censor of the Sonnets to a new platform.

The British Library (@britishlibrary), “From you have I been absent in the spring’ Sonnet 98 forms part of the Fair Youth sequence of Shakespeare’s sonnets, addressed to a young man – something that this edition, published by John Benson in 1640 and on display in #BLTreasures, does its best to disguise.” Twitter, April 18, 2019, 5:42 am, https://twitter.com/britishlibrary/status/1118812016582565888?lang=en.

We will never know Benson’s true intentions, just as we will never know the details of Shakespeare’s sexuality. Nonetheless, the reputation of the scandalous sonnets lives on because of and perhaps in spite of the intentions of their various editors.

Bibliography

1. Hyder Rollins, A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare – The Poems. (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1938), 605. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.262198/mode/2up. 2. Margreta de Grazia, “The Scandal of Shakespeare’s Sonnets,” in Shakespeare’s Sonnets: Critical Essays, ed. James Schiffer, (New York: Rutledge, 1999). Kindle. 3. Rollins, 605. 4. Nicholas Frankel, introduction to The Annotated Prison Writings of Oscar Wilde, ed. Nicholas Frankel (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018), 12 5. Lord Alfred Douglas, The True History of Shakespeare’s Sonnets, (Port Washington: Kennikat Press, 1970), 13. https://archive.org/details/historyofshakepe0000unse/page/12/mode/2up?view=theater 6. Douglas, 20. 7. Lord Alfred Douglas, “Two Loves,” Poets.org, 1892, accessed December 16, 2022. https://poets.org/poem/two-loves. 8. “Manuscript of ‘De Profundis’ by Oscar Wilde,” The British Library, accessed December 16, 2022. https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/manuscript-of-de-profundis-by-oscar-wilde. 9. Edmond Malone, footnote in The Plays and Poems of William Shakespeare, ed. Edmond Malone (London: 1790), 294. https://books.google.com/books?id=nEArAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false. 10. de Grazia, 105. 11. de Grazia, 105. 12. Robert Matz, “The Scandals of Shakespeare’s Sonnets,” ELH 77, no. 2 (2010): 478, accessed December 16, 2022. http://www.jstor.com/stable/40664640.

A full bibliography can be found at https://editingshakespeare.com/2022/12/16/bibliography/

Leave a comment